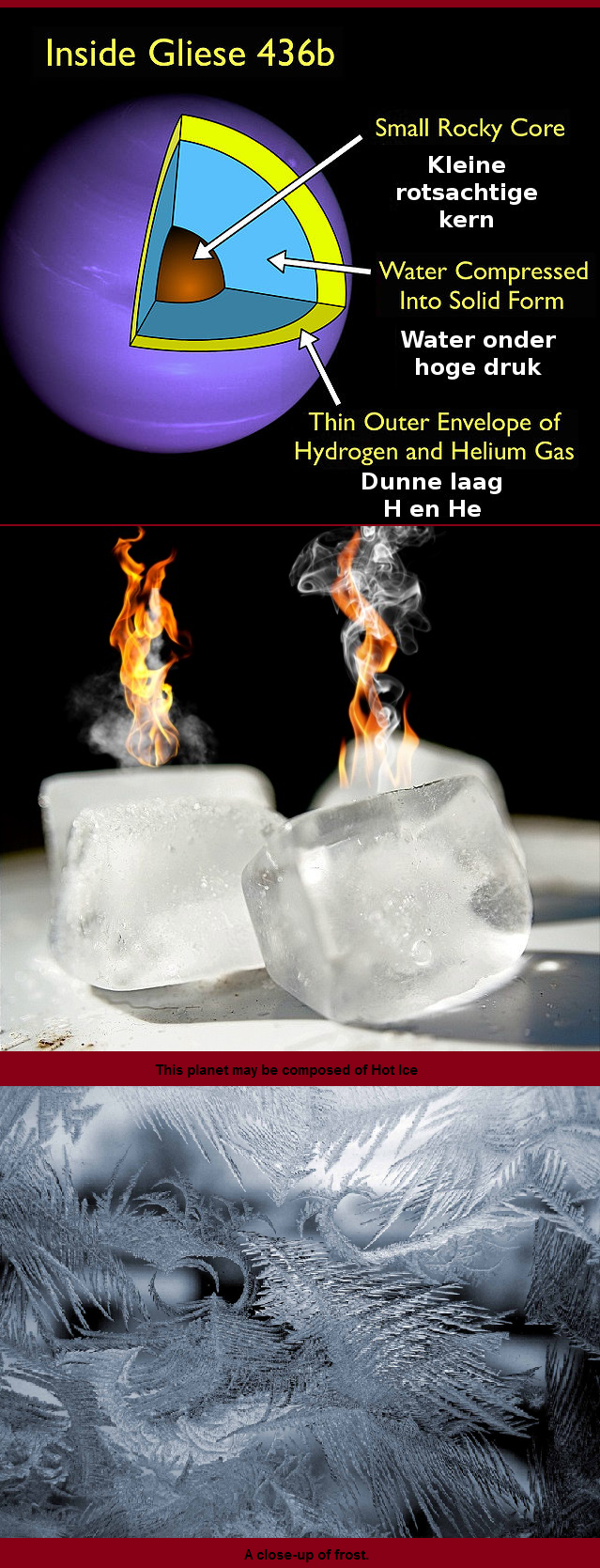

GJ 436b is een exoplaneet die zich op een afstand van ongeveer 33 lichtjaar van het zonnestelsel vandaan bevindt in het sterrenbeeld Leeuw. De gasreus, even groot als Neptunus, onderscheidt zich van soortgelijke exoplaneten omdat er zich in de dampkring geen methaan bevindt.

GJ 436b staat heel dicht bij de ster waaromheen het roteert en om die reden stijgt de temperatuur op die planeet boven de 400° Celsius. Anders gezegd, is het er warm genoeg om water in vloeibare vorm af te weren. Onze huidige modellen zeggen dat een planeet zoals deze, dat wil zeggen: één die voornamelijk uit waterstofgas bestaat, maar tegelijkertijd zulke hoge oppervlaktetemperaturen heeft - aanzienlijke hoeveelheden methaan in de atmosfeer zou moeten hebben. Het omgekeerde is waar.

In wezen heeft het 7.000 maal minder methaan dan het zou moeten hebben. Anderzijds heeft het een verbazingwekkende overvloed aan koolmonoxidemoleculen - en, daarin bevindt zich het tweede mysterie: koolmonoxide zou niet in zulke een grote mate aanwezig kunnen zijn, aangezien het schaars wordt wanneer de temperaturen boven een bepaalde drempel stijgen.

Op het internet vond ik er onderstaande interessante tekst over. Het zijn vooral de mensen, die twijfelden over wat Georges Ivanovitch Gurdjieff over de kern van onze Zon schreef, die ik ermee wens te bereiken. De letters 'GJ' zijn wel niet afkomstig uit de naam Gurdjieff, maar het had wel gekund.

Bovendien zal alles wat Gurdjieff ons ooit heeft gebracht door de gehele mensheid worden aanvaard - ooit. Geef ons nog een duizendtal jaren de tijd, schreef ik reeds eerder. Vanwege het hedendaagse bewustzijnsniveau zijn er vandaag de dag slechts enkelen bereid om een studie te maken van zijn leerstellingen. En, dan heb ik het nog niet over het toepassen ervan. De meesten, die aan Zelfkennis beginnen, liggen er dan ook na enkele jaren uit. Maar, ik ben aan het afdwalen. Sorry!

How Ice Withstands 900-Degree Heat in Space - by Natalie Zarrelli

Out in space, 33 light years away from Earth, a planet called Gliese 436 b orbits very closely to a small, old sun. Its temperature is hot – very hot, reaching over 980° Fahrenheit, but when astrophysicists observed qualities of the planet, its makeup did not seem to make any logical sense. Gliese 436 b is too hot for liquid water to exist, yet its atmosphere gives off large amounts of carbon monoxide, which shouldn’t happen at high temperatures without water present.

Strangely, the solid part of the planet is likely made of ice–the crystalline form of water, or H²O, just as we have on Earth. But anyone who’s drunk an icy beverage on a hot summer afternoon knows how quickly ice can melt. How does this ice become so hot, but remain the solid ice of igloos and cocktails?

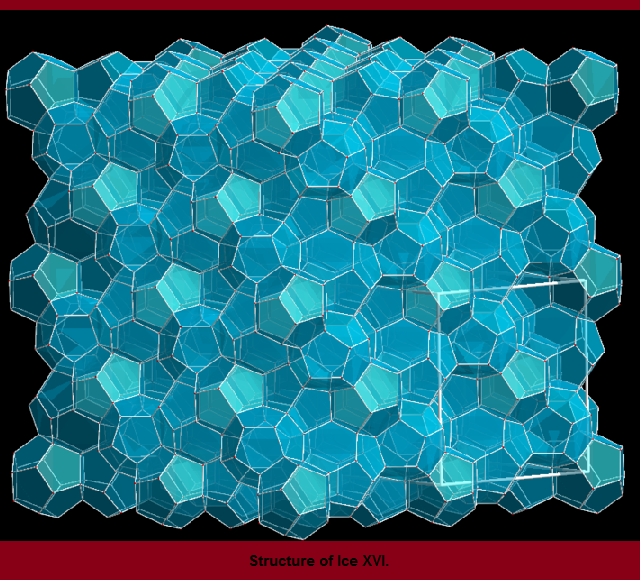

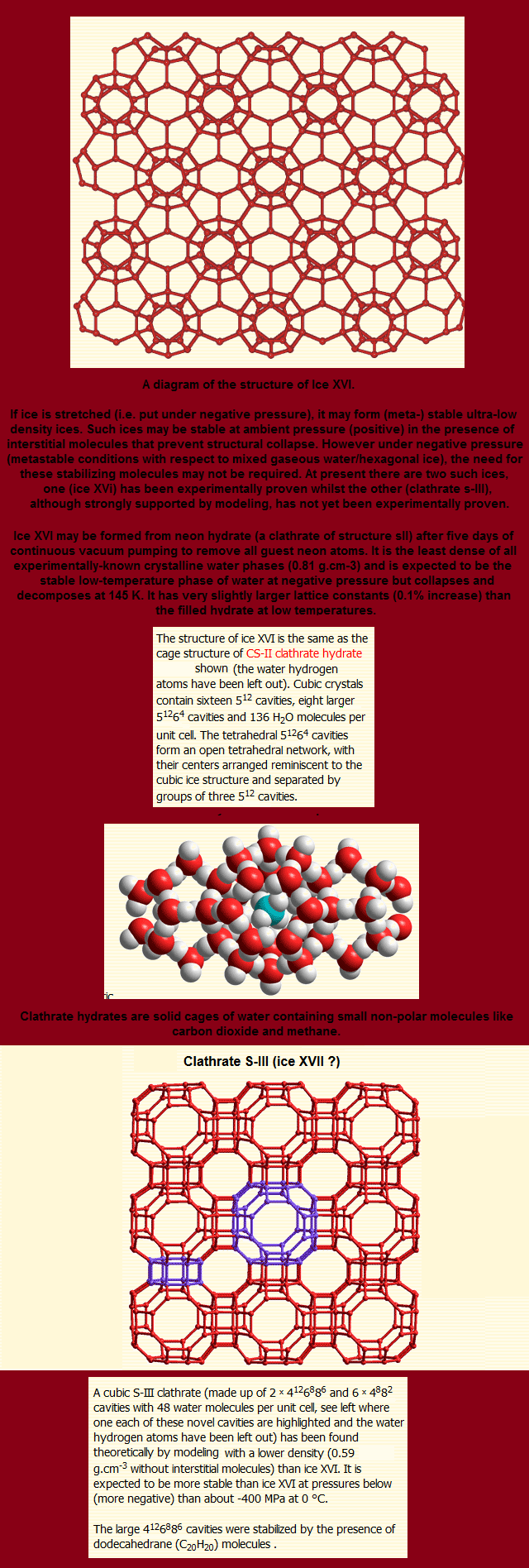

The truth lies in the weird, almost unbelievable world of chemistry and physics: there’s more than one type of ice, made from the same kind of water you drink every day. In fact, there are at least 17 phases of ice that scientists have discovered so far, making ice a far more complicated material than anyone had previously thought.

Scientists have been recreating the conditions to make these unusual types of ice in their labs, including ice X and XVI – the high-pressure ices that scientists believe exist in the burning climate of Gliese 436 b.

It turns out that water, staple of our biological processes and the force behind life itself – is not your typical fluid, having dozens of anomalies. “It is unusual to have so many phases,” says Emeritus Professor Martin Chaplin, at London South Bank University. Chaplin studies aqueous systems, and is author of the most comprehensive ice and water website to date.

Water’s strange anomalies begin with its basic structure: when water molecules connect, they do so with a hydrogen molecule. This bond is so strong that water needs higher temperatures to boil and melt than is normally expected of liquids, and much higher than oxygen or hydrogen alone. Since these bonds can stretch, the distance between the hydrogen and oxygen gets smaller when the temperature rises, and the distance gets larger when the pressure increases.

“This is a consequence of the hydrogen bonding and the relatively low density at low pressures, allowing many more dense structures to be possible,” says Chaplin. The crystal structure of ice Ih, the normal “hexagonal” shaped ice that we come in contact with in freezers and on snowflakes, is also determined by this bond, and in our atmosphere forms a uniform, open lattice of hexagonal crystals.

So when the planet Gliese 436 b is under super high pressure, the ice crunches down, its molecules stretch and compact into new shapes, and its crystalline structure emerges totally changed. If ice X, for example, exists on this hot planet as scientists believe, it is staying solid by forever compressing into a neat, wire-fence shaped lattice. Similar to how water boils at a lower temperature in the mountains than at sea level, at a high temperature under extreme pressure, ice X will need a much higher temperature to melt than when in Earth’s lighter atmosphere.

And that’s just one strange ice phase, all of them unique. According to Chaplin’s website, the disordered pattern of ice VII is likely found on “giant planets and icy moons”, ice VI molecules are aligned in neat triangular grids, and ice V has a molecular structure that looks like a K’NEX toy sculpture gone wrong. Ice III has a wavy, playful crystal structure with molecules that almost seem like they’re dancing, while ice XVI resembles a honeycomb and can actually hold and store different gases. Cubic ice, called ice Ic, likely forms in the highest, coldest clouds of Earth’s atmosphere, and its 3D model looks like point and table-cut diamonds.

Recreating these effects in the lab, as you might imagine, is pretty involved. Before anything begins, ice scientists need conditions which Chaplin says are challenging to create. “It is difficult to produce really pure water,” says Chaplin, and it’s hard to look at the molecules themselves. “At low temperatures, changes in structure can be very slow.”

To study these phases, scientists crush less than a gram of ice into a fine powder, and supercool it using liquid nitrogen. After loading it into a specialized press made of unreactive materials like tungsten steel or diamonds, they slowly heat the ice, degree by degree –suddenly, the ice’s volume will shift, detected by sensors. In this confined space, the position of the water molecules change according to the temperature and pressure exerted on the ice. Scientists look at the molecules using x-rays or a process called neutron crystallography, which uses a small beam of neutrons to form a detectable pattern as they scatter around the ice molecules, giving a three dimensional picture of the molecule.

Recreating these ices in the lab is neat, but it’s also useful to expand our knowledge of the natural universe. “Ices probably exist inside some planets and moons at high pressures, and it is important to know what are their properties...to understand the behavior of those planets and moons,” says Chaplin. “Some ices may form in the high pressure processing of materials and foodstuffs on Earth.”

High pressure ices can also help scientists examine biological cells; freezing at high pressure could keep the ice from increasing its volume and disturbing material while freezing, keeping delicate organic cells intact. Some have suggested that ice XVI could be used to remove methane gas, which produces heat, from beneath the floor of the deep sea, and replace it with less-harmful CO2.

After studying ice structures extensively, Chaplin actually predicted a new phase of ice seven years before it was discovered in 2007, called stacking disordered ice. “One night when I was dozing, in the middle of the night, I realized that this mixed cubic and hexagonal ice structure could be folded up into spherical (actually icosahedral) structures that could explain many of the unexplained, until then, properties of liquid water,” says Chaplin, who couldn’t sleep for three days while predicting the new ice phase. This ice forms sleek, tetrahedral shapes, and is found in high-up cirrus clouds and airplane contrails.

A more sinister phase of ice was predicted, sensationally, in 1960s fiction. Kurt Vonnegut wrote in his book Cat’s Cradle about ice-nine, a disastrous substance capable of turning the Earth’s entire water supply permanently into ice. “I like Vonnegut’s ice nine,” says Chaplin, though on his website, he assures that this fictional version “fortunately has no scientific basis.” (The real ice IV is just a denser version of ice III, and can’t really exist alongside liquid water, or bring about an icy apocalypse).

Scientists are still discovering new types of ice with some regularity, with many more likely to come. In February 2016, chemistry professor Xiao Cheng Zeng proposed that a new low-density ice VIII may exist (though it hasn’t yet been made), which could be the lowest-density ice there is. While Chaplin says we don’t have the capabilities to find some of the extreme high-pressure ices just yet, scientists still continue to look for them.

Next time you make your favorite icy beverage only to watch in dismay as it melts minutes later, remember that somewhere in the universe, that same ice would find a way to stay cool under pressure.